|

articulated locomotives No one really wants the

complication of articulated locomotives! By far the easiest engines to

maintain are those which are rigid: meaning that the driving wheels remain

parallel to the boiler at all times. As traffic increases on a railway,

the company is faced with new problems. More trains can be operated with

existing equipment but this will be limited to the signalling capability of

the line and the number of locomotives available. In addition, more trains

mean more staff who have to be paid and managed.

The alternative is to run

longer trains and this means more powerful locomotives are needed. Here one

will very quickly reach a limit for a number of reasons.

-

The size of boilers are

limited by the loading gauge of the line.

-

Track and civil engineering

structures all have a maximum axle loading so the heavier locomotive will

have to spread the weight over more wheels.

-

More driving wheels limit

the radius of curves that the locomotive will negotiate.

This is when everybody and

their dog gets out paper and start to design their own articulated

locomotive. In fact some designs have been so bizarre that they must have

been designed by the dog! Here we shall restrict our copy to common solutions

found on narrow gauge lines.

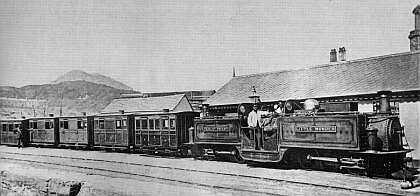

The first narrow gauge

railway to need articulated locomotives was the venerable Festiniog Railway.

The tiny 0-4-0 tender locos built by England were quickly inadequate for much

of the traffic and a new design by Robert Fairlie was built called 'Little

Wonder'. He had supplied double Fairlie locomotives elsewhere which had been

hugely unsuccessful but the new Festiniog engine became a resounding success.

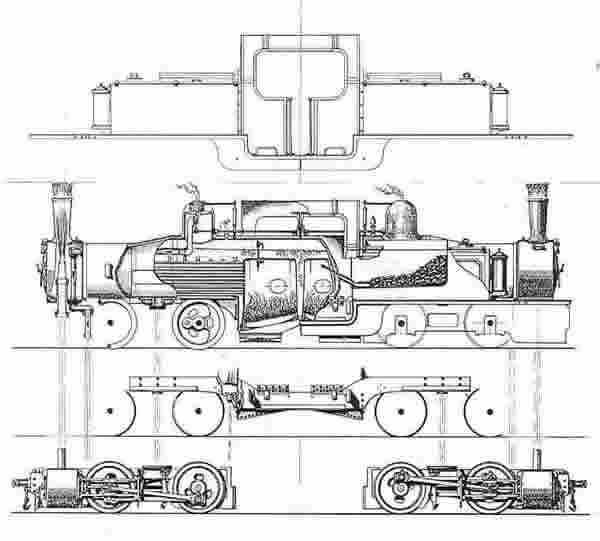

The design consisted of two

pivoting power bogies mounted under a double boiler. This removed firebox

size restrictions but the fireman was presented with twice the work. As with

all articulated locomotives, one weakness has always been maintaining the

integrity of the flexible steam joints but Fairlie did manage to solve many

of the problems.

It is true to say that most

double Fairlie locomotives were unsuccessful and only the Festiniog continue

to use the configuration.

Single Fairlies were

also built and ran on a number of lines.

'Taliesin' an 0-4-4 single Fairlie built new by the Festiniog Railway

Péchot-Bourdon locomotives

were built in France for military use and are nothing more than a developed

Fairlie. Over 70, 0-4-0 0-4-0 locomotives were built and operated with

mixed success. Larger examples were also built.

The original design by Jean

Meyer of France became the most common of articulated locomotives despite

suffering from a problem of not being able to include large fire boxes.

Kitson solved the problem by moving the bogies apart. These engines were

exported around the world and became larger and larger in size.

'Monarch', which moulders at

the Welshpool and Llanfair Railway was originally built for Bowaters Railway

Kent. This is an original Meyer design built by Bagnall. A circular marine

firebox was fitted which did not contribute to its success and 'Monarch' has

become the locomotive that no one wants to operate.

The Swiss, Anatole Mallet,

developed his design as a flexible engine. The rear power truck forms part of

the rigid structure and the front bogie hinges from the rear. A true Mallet

is a compound. That is, the high pressure steam exhausted from the rear

cylinders is transferred to the larger cylinders of the front bogie and used

for a second time. The advantage of the Mallet is that the flexible joints

are kept to a minimum and those that are used have minimal movement.

The disadvantage is that the

front of the boiler overhangs while negotiating curves which reduces

stability and restricts the locomotive's speed.

Mallets were always very

popular in Europe but never really caught on in the UK.

The United States developed

the Mallet into behemoths of staggering proportions. One design even involved a

flexible joint in the boiler (designed by a dog).

Big Boy

The Garratt is the most

famous of all the articulated locomotives and its advantages are well known.

However it does have one very bad characteristic: its length... This leads to

very long steam pipes and other things having to be stretched to vast

distances. There are only two known examples of compounded Garratts, these

being K1 and the Burma Railways loco.

the World's first Garratt - K1 now at the Welsh Highland Railway

newly rebuilt Garratt No 87 at Boston Lodge,

Festiniog Railway

Some really huge Garratts

have been built and the Garratt is certainly one of the most successful

articulated designs. Needless to say, there are a bunch of Garratt

look-alikes which appeared in order to circumnavigate the patent.

A number of designs were also

developed which allow the addition of an extra driving wheel which possessed

some sideways movement. One such system can be found on the NG15 Mikado

(2-8-2). In this case, the Krauss-Helmholtz bogie.

The requirements of logging

railways have spawned a whole range of unique articulated designs.

Locomotives were required to run on terrible track, sometimes, even, just on

logs, climb very stiff grades and be very serviceable. Speed was certainly

never an issue.

Shay locomotive

Shay locomotives had regular

fire-tube boilers offset to the left to provide space for a two or three

cylinder "motor," mounted vertically on the right with longitudinal drive

shafts extending fore and aft from the crankshaft at wheel axle height. These

shafts had universal joints and square sliding slip joints to accommodate

motion of the swivelling trucks. Each axle was driven by a separate bevel

gear, and used no side rods.

Driving all wheels, including those of the tender, together with small

diameter wheels were the strength of these engines, their entire weight

developing tractive effort. A high ratio of piston strokes to wheel

revolutions allowed them to run at partial slip, where a conventional rod

engine would spin its drive wheels and burn rails, losing all traction.

Shay locomotives were often known as sidewinders for their side-mounted drive

shafts. Most were built for use in the United States, while many found their

way to 30 additional countries, territories or provinces.

Although the Shay was the

most common geared locomotive, it had a significant flaw that was not

corrected. Because the drive shaft lies outside the trucks, instead of along

the centreline, truck rotation when following track curvature causes

substantial drive line length change, unlike the central drive shafts of

Heisler locomotives and Climax locomotives. In modern drive shafts, this

effect is accommodated by roller splines instead of bronze slip joints (shown

between "Sonora's universal joints") that lose their ability to slide under

high torque.

Wreck photographs show Shay locomotives, before or after uphill curves, where

they failed to respond to change in track curvature, thereby running off the

track "for no apparent reason." Some texts refer to these locomotives as

"rail spreaders" and "flange hounds," both characteristics of trucks that do

not steer freely under heavy load.

Other disadvantages include the noise of the gearing, and the very low top

speed.

The Climax locomotive has two

steam cylinders were attached to a transmission located under the centre of

the locomotive frame. This transmission drives drive shafts running forward

and rearward to gearboxes in each driving truck.

Unlike the somewhat similar Heisler design, there were no side rods on the

trucks. The gearboxes drove both axles on each truck.

Many loggers considered the Climax superior to the Shay in hauling capability

and stability, particularly in a smaller locomotive, although the ride was

characteristically rough for the crew.

The Heisler locomotive was

the last variant of the three major types of geared steam locomotive, Charles

L. Heisler receiving a patent for the design in 1892 following the

construction of a prototype in 1891. Somewhat similar to a Climax locomotive,

Heisler's design featured two cylinders canted inwards at a 45 degree angle

to form a 'vee-twin' arrangement. Power then went to a longitudinal

driveshaft that drove the outboard axle on each powered truck. The inboard

axle on each truck was then driven from the outboard one by external side

(coupling) rods. The Heisler was the fastest of the geared steam locomotive

designs, and yet was still claimed by its manufacturer to have the same low

speed hauling ability.

|