|

an

account of a trip on the railway |

reproduced

from the Gazetteer

line plan - click on image to enlarge

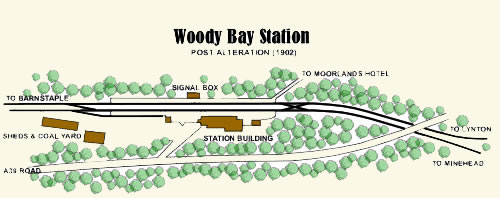

Though Barbrook

is

the connecting station for the L&B and the M&B, the actual junction

is some

two miles closer to Barnstaple, in what may well be the beautiful location

ever mooted for the meeting of two railways, Woody Bay Station.

a double headed special enters Woody Bay en

route to Minehead

The L&B is at this point at the summit of its lengthy climb from Barnstaple,

980ft above sea level, and about to begin an equally sharp, but mercifully

shorter descent from Woody Bay to Lynton; in just over three miles falling

280ft (the majority of this being at 1-in-50). From this attractive station,

set on the high watershed but sheltered by a pleasant copse of trees, both

lines run parallel out of sight through a deep stone cutting. Upon opening of

the Minehead line, little modification was made to the station itself beyond

the replacement of the original signal box with a larger one standing

opposite the station building, and the addition of a double-crossover at the

end of the platforms to allow access to the new line; this junction marked

the official divergence of the Lynton & Barnstaple and Lynton & Minehead Railways, or as they

are now known, the Barnstaple & Minehead branch of

the Southern Railway.

Despite its status as a junction,

the duty of the Woody Bay signalman was little different from those at Chelfham, Bratton Fleming or Blackmoor Gate, as through traffic from the

Minehead line was infrequent, with only a handful of goods trains a day,

accompanied by the occasional passenger working. This was a direct result of

the railways being treated as separate entities that just happened to share a

connecting line, despite the two companies having been intertwined under the

same management for their entire lives.

The cessation of passenger and goods workings to Lynton marked an end to this

arrangement, with the majority of trains now working directly along the

Minehead line. This brought about a reduction in status for the signal box;

as a cost-cutting measure it is now only staffed during peak seasons, with

responsibility for its operation during off-peak months falling to one of

Woody Bay’s porters, or on occasion (for specials and goods trains run at

unusual hours), the train crews. The working practice under these

circumstances is that a key to the box is attached to the section-staff, a

situation that is much to the liking of the staff, as it meant that when

needed, they no-longer have to rely on more ‘ingenious’ methods to gain access

to the box, (as in the days of independence when they saw fit to sortie under

cover of darkness to Pilton yard to ‘liberate’ rolling-stock for operation of

Minehead trains). Details of those ‘ingenious methods’ are undocumented, but

persistent stories repeated at the ‘Halliday Arms’ in Barbrook and the ‘Rose

and Oak’ in County Gate make reference to a series of skeleton and duplicate

keys machined up by a local smithy.

Immediately after departing Woody Bay the two lines vanish round the cutting

and pass under the main road to Lynton. Immediately, the Minehead line begins

to fall at a steep gradient through its own cutting, swinging away from the

original L&B; this marks the beginning of the steepest sustained gradient on

the railway. While the original line continues its gentler descent along the

valley side towards Lynton, the M&B dives fiercely down towards the river, on

a ruling gradient of one-in-thirty-five. While a pleasant enough downhill

jaunt on the through trains of today, return journeys face a hard slog.

Thankfully this steepest portion is shielded from the sea by the surrounding

land and woods, so trains have little else to fear aside from the gradient,

though during peak season and periods of heavy goods traffic there is always

one engine left on duty at Barbrook, should the services of a banker be

necessary.

|

BARBROOK HIGH

AND LOW LEVELS |

Still

falling hard, the railway continues to hug the same side of the valley as the

L&B; when the original survey was submitted to Parliament in 1899 it was

intended that on leaving Woody Bay it would cross the valley and then on an

easier gradient follow the opposite flank to Barbrook, where the West Lyn

river would be spanned on a small viaduct. However, George Newnes, local

landlord, chairman of the L&B, and opponent of both the M&B and its

promoters, the Halliday family, managed to get the bill defeated on the

grounds that this route did not make provision for stations at Barbrook

(being too high above the village) or Lynton (being on the opposite side of

the valley). In order to avoid having to resurvey the entire railway, a

deviation line was quickly planned out; as such, having fallen several

hundred feet in just two miles, trains now coast into Barbrook Station.

The station is preceded by a single span plate-girder bridge over what was

once a farm lane, part of which has now been surfaced to form the approach

road to the station. This marks the end of the steepest decent and the start

of a short section of level track through the platforms.

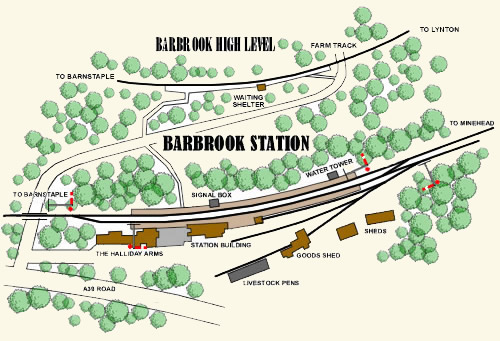

Barbrook was for years (until the closure of Lynton station), ‘Barbrook

Junction’, the terminus for Minehead passenger trains, bar a few exceptions.

Built on twin-levels, it forced passengers who wished to change trains for

Barnstaple (or vice-versa) to negotiate the farm track to the high-level

station, seventy feet up the hillside. For a while a set of stairs were

provided to connect the stations, protected from the elements by alpine-style

wooden gabling, but a series of nasty falls by less-than-sure-footed

passengers quickly led to their removal.

Barbrook High Level, less than a mile up-chainage from Lynton station, was

just an ash-surfaced platform with an austere concrete shelter little

different from that at Parracoombe, originally faced in wood to provide a

more welcoming appearance. A grim and silent place, save for the rustling of

the dripping trees that overhung the line and platform, it was far from

popular with passengers, but a necessary evil. Trains often only called here

by request, and due to a somewhat cavalier nature adopted by Lynton drivers

regarding their Minehead cousins, would often drop off passengers for

Minehead knowing they were leaving them stranded due to lack of motive power

to provide the connecting service.

Barbrook Low Level, or as it is now known, just Barbrook, is a far more

welcoming place than the High Level halt, and a strange atmosphere of

‘busyness’ reflects it’s status as intermediate passing-point on the new

‘main line’. Though the waits between passenger services can be long and

tedious, there always seems to be something on the move, be it a through

coal-train, two trains passing, or just one of the older Manning-Wardle locos

pottering about between turns as a banker, shunting trucks like a much-loved

but aging relative put out to pasture. These however are scenes little

different from elsewhere on the line, and the truth of the matter is that the

buzzing atmosphere is spill-over from the adjacent ‘Halliday Arms’ inn, who’s

patrons regard the station as a convenient extension of the beer-garden. The

‘Arms’, built by a member of the railway-promoting Halliday family to snub

the rival Newnes dynasty, is built in matching Nuremburg style to the station

itself, and being sited adjacent to the main booking-office on the

approach-road seems to have been happily absorbed into the station proper.

In

additional to the station building and its attendant ale-house a copious

goods-shed is provided, along with ample sidings, cattle-docks and sheep-pens

for local wares, along with a few clapboard-and-cement warehouses thrown up

more recently. Two platforms stagger a roomy passing-loop, overseen by the

gables of the station building on one side, and a tidy signal-box on the

other, set back into the cutting wall with a commodious view over operations.

Being the current station for Lynton and Lynmouth as well as Barbrook makes

it also a prime destination on the line for tourists and holidaymakers; as

such it is fully-staffed during the summer months to maintain a crisp and

tidy turnout that is lacking elsewhere on the system. With its trim

flowerbeds and hanging-baskets, freshly repainted woodwork, quaint trains and

the guarantee of at least one Halliday patron sunning himself on the

platform, pint-glass in hand, the station is charming in it’s immediateness

and cosiness.

On this particular afternoon, Friday June 7th 1935, there are several groups

of Halliday’s friends mingling with holidaymakers on the platform. The sun is

high and golden, and the sounds of bees going about their honey-making is a

pleasant bass to the alto-like gurgling of the overflow valve on the large

water-tower adjacent to the signal box, all set to the tempo of Lyn’s

injector-pump as she simmers on the goods yard headshunt. Soon a soprano-like

whistle-cry asserts itself, and with a familiar rattle of wheels on rails Lew

emerges from the cutting marking the start of the climb to Dean Steep and

crosses the road bridge into the station. Behind her follow three coaches,

including (to my pleasure), ‘the special’; another product of the spats

between the Newnes and Halliday families, ‘the special’ was a private saloon

built at Pilton Works from an old coach body. Now designated as the

first-class observation saloon, it includes an open section at the Minehead

end from which a commanding view can be attained over the splendid scenery,

the railway, and the engine at work.

There is no immediate rush to board the train however. Most of these

passengers are headed in the opposite direction, and so while a few

overzealous souls scramble to claim seats, Lew’s crew uncouple her and (with

a wave from the signalman) they and their engine disappear off down the line

on some secret mission, quickly running out of sight round the curved

platforms. A deeper-throated American chime whistle sounds out, and Lyn,

proud product of the Baldwin Workshops in Philadelphia, eases from the

headshunt, and through a series of reversals and point-changes, finally

coupling smoke box on to the train, ready to draw us onto Minehead. Her tanks

are full to brimming and her bunkers are well-coaled, and once again it seems

departure is imminent, but even as part of the mighty Southern Railway this

narrow gauge line dances to it’s own tune, and while waiting for the guard

the chance makes itself to have a friendly word with the crew.

It’s a pleasure to find Johnny Shobdon on the footplate. A veteran driver and

a wry wit he’s known as an artisan and craftsman of the highest order, and

this talent with his hands has resulted in some exceptional models of the

railway’s locomotives and rolling-stock.

Soon the guard emerges from the tap-room of the Arms, a basket swinging from

his hand. This has been stocked with bottles of chilled water and various

tonics, all to be kept chilled in the guard’s compartment. He’ll be offering

them to the passengers along the journey (for a reasonable fee of course), as

many will underestimate the effect Devonian (and Somerset) sun can have on a

dehydrated body. By this point anyone who had hurried to board the train has

disembarked back into the throng on the platform, and a sudden burst on the

guard’s whistle sparks a second rush. Those familiar with this routine

(myself included) will have already gotten into the special’s open-sided

compartment, and with a second signal from the guard and a response from the

engine, the train sets into juddering life towards Lynton.

|

VIADUCT QUARRY AND QUARRY

VIADUCT |

Falling once more at one-in-forty-four, Lyn

quickly gains speed down the gradient. It can seem alarming at first, but

Johnny knows his steed and her road in the manner that only years of

familiarity can breed, and with brief touch on Lyn’s brake we thread the

needle of the first road-bridge over the line (Station Hill), then emerge

from below Knibswothy wood and clatter into the outskirts of Lynton, with

houses below and above us. A pair of gentle reverse curves brings us to the

bottom of the gradient and an unofficial stop, Viaduct Quarry, a small quarry

opened out during construction of the line to provide stone for the

earthworks. The formation here is very wide and convenient for Lynton town,

as after Newnes raised objections to the original route, a station was to be

built here, hence why smarter passengers may tip driver or guard a wink (and

a shilling) to drop them off here rather than face the uncomfortable

charabanc connection between Barbrook and Lynton.

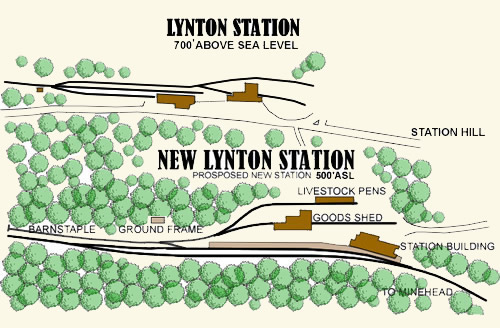

Due to another about-face by Newnes when his

obfuscation failed to prevent the passage of the railway through parliament,

‘New Lynton’ station was never built, but there is word about that the

Southern Railway may be considering relocating the station buildings from the

former Lynton terminus to this site to better serve the holiday traffic.

Easing travel for the locals is a secondary benefit as far as Eastleigh is

concerned, but it is felt in the area that if this step is taken, it will

demonstrate a long-term commitment on the Southern’s part to the railway’s

future.

Today however there is no-need to stop, and

Johnny gives Lyn a burst on the regulator as we accelerate through the

overgrown shunting-loop and sweep hard right (with a flash of sparks from the

guard-rails) out of the quarry and onto a high embankment that leads to the

first of many dramatic pieces of engineering on the line, the crossing of the

West Lyn valley on the Glenlyn Viaduct.

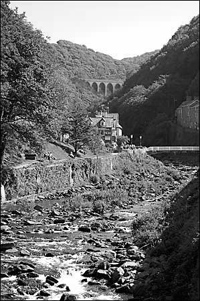

the Glynlyn Viaduct from Lynmouth

One of seven viaducts on the line, Glenlyn (or to the railwaymen, ‘Quarry

Viaduct’, a rather confusing but amusing reversal of the name for the

unofficial halt that precedes it) was the first to be built, with the

railway’s ‘cutting of the first sod’ ceremony taking the form of laying the

viaduct’s first foundation stone. In this location, exposed to the sea,

construction was arduous, particularly when building the arches, diverting

much-needed time and finance away from the other viaducts which had to be

finished ‘on the cheap’ with timber decks carried on brickwork piers (the

wood later being replaced with wrought-iron). The result however is a

striking masterpiece wrought in salmon and cream brick, striding 81ft high 930ft across valley, road and river with an Olympian certainty in

its fourteen-arched-step. Poised on the lip of the valley’s final plunge down

to Lynmouth, the viaduct is highly visible and a local landmark. For

passengers, an unobstructed view may be gained over Lynton below and Lynmouth,

the Bristol Channel, and the Welsh coast beyond, a highlight of the trip.

Immediately after clearing the

viaduct’s eastern parapet we swing back left alongside the valley, passing

yet another small quarry and what Lynton drivers once mockingly referred to

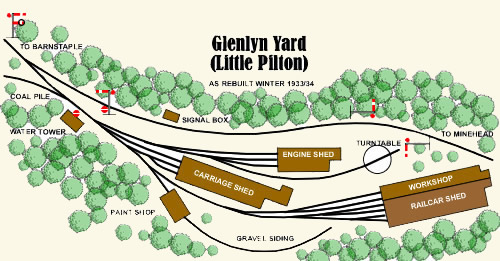

as ‘Little Pilton’, Glenlyn shed, the main locomotive facility for the

Minehead line. When this section of the railway was opened in 1902, a

two-road carriage shed and a short engine shed large enough to hold three

locomotives were provided here, under the misconception that when ‘New

Lynton’ was built, this would become the operational centre of the railway;

as seen this never occurred, and Glenlyn was allowed to deteriorate. Other

facilities included a small turntable and a single-road building known as

‘the shop’, which mostly served to house a growing number of discarded or

broken tools and parts, indicative of the derision in which Barnstaple crews held Glenlyn.

Now however the yard has seen a transformation; with new locomotives and

rolling stock arriving throughout the last decade, and land for expansion in

Barnstaple and Minehead being lacking, the Southern has opened out the quarry

for ballast and used the land created to expand the Yard. Today, ‘Little

Pilton’ is on par with its namesake in terms of importance. Both engine and

carriage-sheds were enlarged, ‘the shop’ has become a dedicated paint-shop,

the turntable was replaced with one of larger diameter, and in the winter of

1933/34 a facility was established to maintain and house the new railcars

that are being introduced to the line.

From the end of the viaduct a

single spur off the main line fans out to serve the engine

and carriage sheds. A siding extending along the side of the

carriage shed, previously used solely for storing ‘junked’ rolling stock, has

been extended and re-aligned into the new railcar facility, a six-road

building, two of the lines being separated off from the running-shed in a

dedicated workshop with specialist maintenance equipment. Against the bank is

another large water-tower and an ample coal pile, where Lew is taking

refreshment after bringing her train this far from Barnstaple. In the shed

Lyd, one of two ‘Baltic’ tanks obtained from North British for the extended

railway in 1901 (her sister machine being Axe), simmers idly; having just

undergone a heavy overhaul, a slow fire is being built in her to check for

any boiler leaks.

staff pose at Glenlyn

As noted, Glenlyn was not well provided for at first, but as Lyd will

testify, can now undertake major overhauls; indeed the new workshop has

become the railway’s premier maintenance facility. As the enlarged engine

shed can comfortably hold six ‘larger’ engines, the Baltics and the two

Mallet tanks built by the Southern (River Avon and River Brue) are maintained

and shedded here, in addition to the newly arrived Armstrong-Whitworth diesel

River Avill. Scenically, Glenlyn also boasts an unrivalled location

overlooking the valley, made all the more picturesque by the immediate

proximity of the viaduct; were a ‘New Lynton’ station built directly across

the viaduct from the sheds then this would be a railway location of beauty

unsurpassed in Britain, but whether this becomes a dream or reality remains

to be seen.

|

EAST LYN VALLEY TO

WATERSMEET |

With those

same magnificent views still in sight off to our left, Lyn accelerates along

a wooded ledge cut against the hillside, eventually swinging round many

hundreds of feet above Lynmouth to enter the East Lyn valley. From the road

through the valley bottom the train can only be perceived as a high line of

steam following the wooded counters, then winding and twisting along the open

flank of Oxen Tor which rises overhead with a majestic solemnity. Rolling

over gentle downhill gradients, through rock cuttings and thick trees, Lyn

leads us on, seemingly through not only space but time into some primeval era

of British history.

"wooded ledge cut against the hillside" -

photo - Glenthorne Estate

This mile-and-a-half of line is among the most inaccessible sections of the

railway due to its high position relative to the surrounding roads, and only

the occasional intersection of railway and footpath serves to break this

sense of isolation. These crossings are all unofficial halts, like Viaduct

Quarry unmentioned in any timetable, but blessed with evocative names such as

Lyn Cleave, Summer Hill, For Wester Wood, and Myrtleberry Crossing. The last

is very popular among the cannier holidaymaker, as there is much of interest

to be found in Myrtleberry Cleave, especially to those of an archeologically

or historical pursuit, chief among them Iron Age fortifications and the

remains of some long abandoned iron mines. With the coming of the railway

attempts were made to reopen these workings to supplement the traffic

returns, but the ore yielded was of a most inferior grade and the venture

collapsed as quickly as it had been mooted.

In addition to these human items of interest, the landscape is itself of a

most attractive character, and dismounting at Myrtleberry Crossing, three

miles from Dean Steep provides a more convenient access to such wonders than

the official station of Watersmeet, some twenty-five-chains up the line.

the Myrtleberry Tearoom from the

station platform - photo - Glenthorne Estate

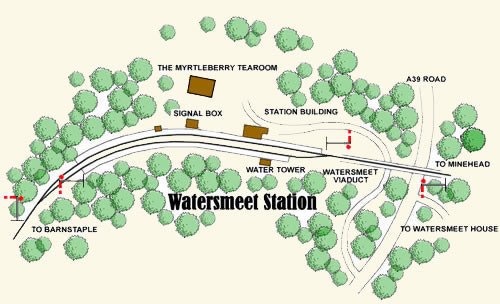

The approach to Watersmeet features a pair of

impressive curves, first swinging us north, then back onto the original

eastern bearing. Check rails were laid in here with good measure, and so as

we grind our way round the second curve into Watersmeet the smell of hot

metal is evident in the air. Johnny shuts off steam well before we reach the

station throat, and the resistance of the coaches through the curve is enough

to bring Lyn to a stop with but a touch on her handbrake to firm the deal.

Regular passengers now crane their heads from windows to observe a series of

arcane gestures and hand-signals between driver and waiting stationmaster –

there is almost always a passing of trains at this station, and judging by

how the stationmaster is tapping his fob-watch it seems the other train will

be some time yet, so we might now (if we choose), dismount to stretch the

legs and savour the atmosphere while we await the passing train.

On closer examination the long-suffering

stationmaster is red-in-the-face; a recent transfer from some vital outpost

of the Southern network he is used to timetables being adhered to with

religious fervour, and his displeasure at the lateness of the ‘up’ train is

evident. Johnny however is far calmer, choosing to stuff his pipe and

remarking with a philosophical bent that the delay is no doubt ‘the work of

The Beast’. Judging by his contented puffing we have a few minutes at least,

so an exploration of the station seems in order. With heavy forests flanking

the hillside station above and below, the impression is given of staring down

a narrow corridor with only a thin slice of sky visible above; ahead of us

the line runs straight and true, springing across the second viaduct on the

line to the portal of the first tunnel at the foot of another high and wooded

flank of Exmoor. Overall the impression of the station and little train in

such a large landscape is both quaint and impressive, lying somewhere between

alpine splendour and the green and pleasant land.

this section of the line suffered landslips

Opened in 1906, there is no local traffic at Watersmeet, and it was built

primarily to provide a more convenient passing-point between Barbrook and the

next loop at County Gate. The passing-loop for this section was originally

some two miles further on at Brendon, but when that proved to be

operationally inconvenient, it was relocated here. Since trains might often

be kept waiting (as we now find ourselves) it was thought best to provide

passengers with the means to dismount and stretch their legs, and so the

station manifested.

The facilities at Watersmeet were once little better than those of Barbrook

High Level, yet in contrast to that dismal halt this is now among the

prettiest stops on our journey (though it is safe to say that few of the

stations are anything less than beautiful). Comparisons are often made to

Chelfham on the Lynton-Barnstaple section, with a proper and complete station

building of charmingly tiny size, two platforms and an equally modest signal

box with the associated array of semaphore signals. In 1910, the same year

that the Glenthorne Hotel opened at County Gate, a tearoom was established by

the Hallidays adjacent to Watersmeet Station, ‘The Myrtleberry’, which does

good business from walkers and explorers who have made this their

station-of-choice for exploring the East Lyn Valley.

The greatest attraction in the area is

Watersmeet House, built in 1832 by another member of that familiar brood, the

Reverend W.S. Halliday. Seemingly the good reverend enjoyed pastimes of the

body as much as of the soul, as Watersmeet House was commissioned

specifically as a fishing lodge. Thrown open to the public by the Hallidays

some years ago, it now makes a fine earning as a sister tea-room and shop to

the Myrtleberry. The fishing, incidentally, is excellent.

As we return to the station a

deep-voiced cry chills the air. As we look along the line for the source of

this whistle the nose of an engine emerges from the distant tunnel. The

locomotive crosses the viaduct with a great show of steam and noise and

swings over the points into the up-platform, revealing its prodigious length

and size. It is a monster of a machine to those accustomed to the barking

little locomotives so beloved of this area, an iron dinosaur snorting and

breathing anger and defiance as much as it does steam and smoke. As it comes

alongside our train three ominous digits can be seen painted on the cab side,

‘666’. This is ‘The Beast’ to which Johnny earlier made reference.

'River Avon' at Barnstaple circa 1930 - photo Southern Railway

In the 1923 grouping the Southern

Railway found itself lumbered with nearly fifty miles of run-down

narrow-gauge railway which promised only small returns. Tied to the railway

however, and determining to make the best of its lot, the men of Eastleigh

and Waterloo have in recent years begun experimenting with new technologies

to streamline and improve traffic on the ‘Lynton and Minehead’ branches. The

first of these experiments was number 666, delivered in 1925. Seeking to get

a more powerful locomotive onto the line, in order to do away with the

expense of double-heading, Eastleigh Works took the design elements of the

‘classic’ Manning-Wardle tank-engines and expanded on them to produce an

0-6-0+0-6-0T Mallet articulated tank-engine, which promised a huge surplus of

power without sacrificing the ability to negotiate sharp corners, a

not-dissimilar principle to the highly successful ‘double-Fairlies’ of

Festiniog Railway fame. Things however, did not go as planned.

The locomotive numbered 666 seemed cursed by ill fate from the second it

touched the metals of its new home. Eastleigh had dubbed upon it the name

River Avon, but no-one on the railway would refer to it as such, as there was

already an ‘Avon’ on the line, the County Gate station cat! In trying to find

an alternative moniker for the engine, it became known as ‘The Mad Mallet’.

Though harmless enough in itself, this name soon seemed justified as a run of

ill-luck continued; not long after entering service a man riding (in

violation of regulations) on the engine’s leading platform was thrown off

during shunting at Blackmoor Gate and suffered several broken bones. An

embankment collapsed under the unprecedented weight of the machine, it spread

the rails, rode roughly and proved extremely temperamental (track ties were

very quickly installed where rail spreading had occurred).

The culmination of these

unfortunate events however happened one year to the day of its arrival.

During a thunderstorm, while working a night train of coal down the fearsome

Porlock Incline, 666’s train managed to separate.

666’s driver, feeling his vacuum brakes come on, moved quickly to safely

check his remaining wagons, coming to a halt a few hundred yards down the

line, and sent his fireman back up the incline to find the rest of the train.

Meanwhile the guard, though realising his situation, panicked and chose to

run down the line in the hope of finding his engine. In his rush, he failed

to pin down the handbrakes on his stalled trucks, with the result that once

the vacuum brake system ‘bled off’, the weight of the train on the gradient

overcame the brake in the van. Disaster was unavoidable.

The surrounding storm and fury made a comprehensive account of what followed

impossible, but the runaway trucks soon overtook the guard, shot past the

fireman and collided with the leading section of the train at nigh on thirty

miles an hour. The driver was seriously injured and all of the train was

smashed to matchwood, except for number 666, which escaped relatively

unscathed. The sinister coincidence of the date, coupled with the horror of

the disaster, was the icing on the cake. What had once been nicknamed ‘The

Mad Mallet’ was now and hereafter ‘The Beast’ and only the most confident (or

foolhardy) of crews would drive and fire her.

Not long after this ‘incident’, engineers from Eastleigh arrived at

Barnstaple to learn about how the new engine had fared in a year’s service.

Reports were not flattering. Somewhat abashed, 666’s designers made quick

amends to rectify what design flaws they could, and the second Mallet, 667

River Brue, was found to be a much improved machine upon delivery in November

1926, the key change being the addition of leading and trailing pony trucks

to steady her riding. Quickly she became the baby of the loco crews, as

beloved by them as much as her sister was reviled, the ‘Beauty’ to Avon’s

‘Beast’.

Ironically, in the years that followed there was a reversal of character

traits, as Brue began to display fits of ‘pique’ (riding roughly and with a

pronounced gait, derailing at points and breaking vacuum pipes) whereas Avon,

after modifications during a 1929 return to Eastleigh to match Brue’s

specifications was surprisingly tamed into a superbly reliable machine.

Although wags attributed Brue’s behaviour to the loco crews ‘spoiling their

little princess’, her troubles were traced to a set of poorly-profiled

wheels, and once these were replaced, both Avon and Brue have settled down

into model citizens..

Post Script: Since ‘Avon’, the station cat at County Gate, passed away in December

1934 at the venerable age of 19, crews have finally started to give River

Avon her due by referred to her by her given name. However the names ‘Beauty’

and ‘Beast’ have continued in use in the manner of affectionate nicknames.

|

WATERSMEET TO

SCOTCH CORNER |

With an exchange of whistles and a

series of frantic summonses by the guard, Avon heads off towards Barnstaple,

a long rake of goods trucks behind her. Lyn however, raring and ready to go,

sets off immediately up-chainage, charging furiously over the level back of

the Watersmeet Viaduct. Clearly Johnny wants to get up some speed before he

has to close off the blower and reduce steam through the tunnel.

Watersmeet Viaduct stands some 78 feet above the level of the river, and its

eastern parapet marks the start of the long climb to the summit at Porlock

Tunnel. Long, slender and graceful, the viaduct consists of twelve

seventy-foot spans carried on tall pillars of pinkish-red brick. Its total

length is some 870 feet, and it has been referred to as ‘The Crymmach Viaduct

Of England’, being a masterpiece of skilful iron and brickwork. From above,

passengers may catch brief but stunning vistas down into the valley, before

Johnny gives a long cry on Lyn’s whistle. Now anyone sticking their head out

of a carriage window must get back in sharpish or risk getting a very black

face indeed, for Lyn comes off the viaduct's final span only to dive straight

into the 164-yard Watersmeet Tunnel.

Unventilated and curved, the tunnel

can only be described as a smoking hell-hole, a horizontal furnace flue

through which trains are boldly whisked, and it is not without some relief

that we emerge from the far portal into blessed daylight once more.

Immediately the train bears hard left and plunges into a sheer-sided cutting

– this is the deepest cutting encountered so far on our trip, and its high

sides are green with climbing mosses and creepers. Suddenly the cutting seems

to fold back, and the southward sweep of the valley is revealed to us, deeply

wooded with pastoral fields and bare moors above, much like the bald summit

of a monk’s head.

Striding on and now laying into the gradients, Lyn leads us straight on

without stopping through the small halt for the hamlet of Wilsham; rattling

through the fingers and knuckles of the valley we soon pass a second simple

waiting-shelter for Rockford. Throughout we seem to be falling towards the

river, but this is an illusion, for Lyn is scrambling up a continuous stretch

of 1-in-78, and it is in fact the river rising to meet us, so that by the

time we reach Brendon station, we are much closer to the valley floor, low

enough that river and rail might share a greeting and handshake.

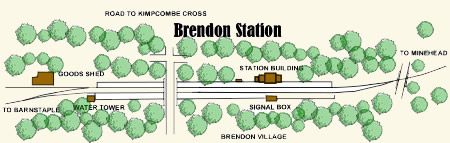

Among a copse of conifers, Brendon station is another gem, and though now a

shadow of its former self, seems to have benefited. Arriving from the west we

first pass the now derelict goods shed, wharf and cattle dock, and beyond a

bridge carrying the Kimpscombe Cross road over the single line we finally

arrive at the station proper. The expected station building is here to our

left, a twin of that at Bratton Flemming on the L&B, and to our right a

pleasing view opens over the houses of the village.

early days at Brendon

As noted at Watersmeet, Brendon was

originally intended to be the intermediate passing-point between Barbrook and

County Gate; as such two platforms were provided along with a lengthy loop

that extended under the road-bridge, broken with a crossover enabling part of

it to be used as a goods loop. However, since County Gate is only 1.5 miles

away, with Barbrook being 5 miles in the opposite direction, it was quickly

observed that westbound trains were forced to wait a considerable time to

cross.

Brendon as originally built

As such, once the railway was open

throughout and funds made available, Brendon’s passing-loop was moved to

Watersmeet and the second platform made derelict. The goods loop remained

however, but although Brendon village has kept up a regular flow of

passengers through the years, goods traffic has always been light, and so the

loop was removed and the goods yard closed by the Southern Railway as part of

a cost-cutting purge in 1932. Today Brendon has no loop or siding, and the

former Signal Box is now a conservatory in which the stationmaster grows a

fine crop of tomatoes. The station itself is operated as a manned halt, with

a minimum staff of the stationmaster and his wife, who also acts as ticket

officer and parcels clerk. They’ve made a comfortable home for themselves in

the station building, and Brendon continues to win prizes in the Southern

Railway’s vegetable and flower-growing competitions, the former ‘up’ platform

now being replete with a magnificent display of colourful blooms.

Brendon in later years.

There are a few local passengers

trickling onto the platform, but they’re not boarding just yet; they’ll be

waiting for the fast railcar-service to Barnstaple, due to pass us ahead at

County Gate. So after setting down a handful of tourists who wish to take in

the pleasures of Barbrook, Johnny gives Lyn a full head of steam and she sets

off under another road bridge with a will, once again climbing with the

gradients up the valley. The river has eased off its own ascent momentarily,

so once again we begin to gain ground on it, scrambling up the hillsides

through a long section of straight track to where we round a long sweeping

corner, high above the river.

This curve, ‘Scotch Corner’ to the railwaymen, is not particularly tight or

arduous, but it is treated with respect by drivers; passengers who seek

explanation would do well to look down into the valley towards Southernwood

Farm, and they’ll see a strange furrow torn into the ground, like a

grassed-over gash leading down from the railway, all the way to the

riverside. This is the grave-marker of the contractor’s locomotive

Kilmarnock, and the source of Scotch Corner’s name.

Kilmarnock was a diminutive 0-4-0ST built by Andrew Barclay & Co. in

Scotland, owned and used by Nuttall’s in the construction of the Lynton &

Barnstaple. After the contractor fell into bankruptcy, Kilmarnock was left on

the hands of the L&B, and would have most likely been sold for scrap had they

not in turn leased it to McAlpines for use in building the Minehead line.

After this seeming reprieve however, Kilmarnock met an unfortunate end one

day in 1903, when the construction office received an unfortunate message

that ‘the wee engine’s taken a bit of a jump into the valley’.

As it had transpired, a slab of stone had fallen from the wall of the ledge

on which the railway is carried at this point, and in the weak light of

morning, Kilmarnock’s driver had not seen the obstruction until too late;

whilst no-one was hurt, the engine was thrown off the line and, train in tow,

careened down the hillside and drowned herself in the river. To this day

there are occasional rockfalls along this section, and making a daily

inspection to prevent a second derailment at Scotch Corner has fallen to the

County Gate track-gang, known on the railway as the County Gate Desperados.

Some of the Desperados are just ahead now, checking on a recently relayed

section of track and ensuring the ballast is packed firmly, and so Johnny

eases off the power and eases Lyn past at a respectable walking pace; he’s

got no need for speed at this point, as he’s almost at the lip of a short

falling gradient and can afford his engine a breather. As he passes the

track-gang he affords them a wave and a salute on the whistle; most crews on

the railway hold the Desperados in high respect, as few other track-gangs on

the line have to deal with such a lengthy or arduous section (Watersmeet to

the Summit, including the lengthy Porlock Tunnel). Their task is furthermore

made difficult by frequent manpower shortages, yet through good humour and

hard work, they always manage to keep the trains running to time, on as

smooth and even a permanent way as could be asked for.

As we leave the Desperados behind, Johnny gives another whistle, and an

unfamiliar croaking blare answers back, the sound of an air-horn. Passengers

who noticed Kilmarnock’s trail of destruction are now rewarded with another

curious sight; below us and at right angles, a second railway line emerges

from a tunnel and crosses the river, before swinging hard right through a

small yard to parallel us on the opposite side of the valley. This is the

Light Railway of the Glenthorne Harbour Authority, opened at the same time as

this section of the M&B. On the curve is a small wooden platform, at which a

few passengers are disembarking from a curious contraption; two former coach

bodies connected by articulated bogies to a central diesel-power unit; the

Glenthorne Railcar. Painted in a maroon and cream livery it looks both

careworn and unserviceable, yet can still put on a surprising turn of speed;

many a driver has been tempted to race it to the junction round the corner at

County Gate, but Johnny’s got no such urge; he knows that the County Gate

signalman must always give priority to the harbour line. So as the railcar

sets off and draws ahead he continues to let Lyn roll on at her own pace.

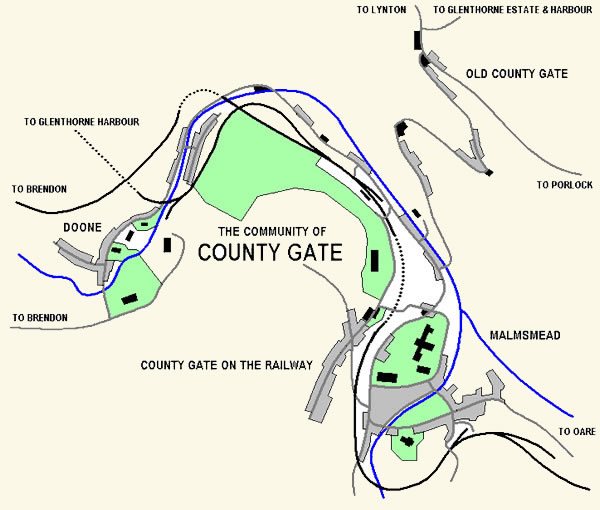

Beneath us in the valley’s bottom are a cluster of houses. One of two

worker’s villages provided for employees of the Glenthorne Harbour Authority,

this one carries the simple and poetic name of Doone. The other is the

village of County Gate (or more properly County-Gate-On-The-Railway, as it

appears in the census), but we’ll get there shortly.

The residents of Doone were first provided with little else beyond a small

shop and a Catholic Church, built in 1909 for the harbour’s sizable number of

Catholic employees and dedicated to Saint Thomas Aquinas, the Patron Saint of

Education. Appropriately enough, the Hallidays shortly thereafter provided

finance to establish a school in Doone for the children of their staff, which

has had to enlarge as children from surrounding villages are now welcomed. In

addition a public house has sprung up, ‘The Lorna Doone’ and lastly the

Alberry School, a small manor house built as a retirement home for a wealthy

entrepreneur, who has since developed it as a school for the training of

guide dogs.

As it is well served by the Glenthorne Harbour Railway, no halt is provided

on the main line for Doone, and so as we skirt the picturesque little

model-village we have no need to stop, and once again Johnny shuts off the

blower and his fireman closes the fire doors as we swing into the hillside,

first through a deep and sudden cutting, and then into the second tunnel on

the railway. Ashton Cleeve Tunnel is only 109 yards long, but it is tightly

curved, swinging us around through almost ninety degrees. As with the others,

it is unlined, and from its rough-hewn rock portal we emerge from the wooded

hillside onto the East Lyn viaduct, widely regarded as the prettiest on the

line, perfectly scaled to its setting and a sure draw for the eyes of people

travelling through or above the valley.

'River Avill' crosses the

East Lyn Viaduct during its trials in 1935 - photo Armstrong Whitworth

As we reach the end of the viaduct the Harbour Railcar passes beneath us on

an arch built into the parapet and skirts around through the fields, while we

coast down a short section of 1-in-40, Johnny gently braking us to a stop at

the home signal for County Gate.

This entire section of railway was not included in the original survey; as at

Lynton, George Newnes managed to get the initial plans rejected in the Lords,

though in this case his intentions were not disguised as being in aid of the

proletariat. A short mile along the valley from here, the railway was to pass

across the valley from Oare Manor, and Newnes was able to convince the

residents that the railway would not only be an eyesore, but devalue their

property, and so win them to his cause. In fighting back, Halliday agreed to

a deviation that would take the railway behind the manor, and also the

provision of a private halt. As with Lynton however, the deviation would

require a break in the carefully surveyed gradients and several substantial

works, two of which, Aston Cleeve Tunnel and the East Lyn viaduct, we have

already seen.

As we wait at the signal though, it’s difficult to imagine the hard-fought

political battles which were waged over the rights to put a railway through

this peaceful landscape. To our left opens out a view over open fields down

to the valley floor, and to our right is the pleasant slope of Southern Wood.

Deforested as a source of timber when the railway first arrived, the hillside

has subsequently become part of the grounds of the Glenthorne Hotel, and

replanted as an extensive arboretum. Trees have been carefully chosen and

composed to form a idyllic scene (and to hide the station from the hotel)

through which guests might wander at ease, though woe betide any who damage

the plants, as the hotel’s head groundskeeper is zealously (and rightly)

protective of his charges.

A timeless moment later, the signal arm shifts to ‘clear ahead’, and with

another cheery toot on her whistle. Lyn eases us forward into County Gate

Station, straight through the loop throat, then over the junction with the

harbour branch that sweeps up from the left, and finally into the platform;

the Harbour Railcar is in its bay to our left, her driver at an open hatch in

the power unit, working on the two Gardner diesel engines inside, and by the

persistent sound of hammer against metal and colourful language dying the air

blue as surely as the accompanying clouds of diesel, having a hard time of

it.

the first railcar, no 200,

arrives at County Gate from Lynton

Also waiting for us in the ‘up’ platform is another railcar, this one in a

striking aquamarine livery, the bold legend SOUTHERN and Atlantic

Airstream painted in trim yellow

down its flanks. This unit, 303, is one of five railcars currently in use on

the railway, the result of an experiment which has left many on the line both

excited and apprehensive, the introduction of diesel power to supplement

steam. Welcomed by most and decried by some, the presence of diesel traction has

become more apparent in the past year; as the production railcars are of

identical design and use standardised parts, Eastleigh has been able to

deliver two batches in just an eight-month period;

301-303: Three-car units (delivered October 1934)

304-305: Four-car units (delivered May 1935)

railcar 302 alongside the

Glenthorne railcar at County Gate

Prior to these units being delivered, two separate prototypes (200 and 201),

delivered in January and June of 1933 respectively, were tested on the line

as proof-of-concept; having demonstrated themselves a success, both have now

been sold to the Glenthorne Harbour Authority to supplement their passenger

services to Glenthorne Harbour and Porlock, where they earn a respectable

living transporting local passengers and tourists. The harbour service

however, operated mostly by the careworn vehicle in the bay platform, is all

about tourism, with many being willing to pay a pretty penny to enjoy the

spectacular cliffside route, overlooking the sea. We shall be getting a

chance to view this sight ourselves shortly, though (thankfully) without the

added thrill of charging along in a lightly-built railcar that creaks on

every turn, and who’s driver has a worrying tendency to drive his charge

onwards like a chariot in the Coliseum.

The main-line unit adjacent to us, the aquamarine 303, makes a far braver

sight, indeed, since we are leaving our train here, we can indulge ourselves

in studying her closer, for now with a wave and a whistle, Johnny sets Lyn in

motion once more, and leaving us behind she steams away from the station and

out of sight under the road bridge leading to County Gate village; moments

later her vibrant exhaust is muffled by the tunnel beyond the road bridge,

and abruptly silence returns to the station, broken only by the steady thrum

of 303’s engine, and the not-so-steady belches emitting from the Glenthorne

Railcar as its driver (with judicious application of hammer and quite an

impressive war-cry) finally persuades its second Gardner engine to fire. Due

to being constructed from whatever was to hand, the railcar features two such

power-plants; each with 3 forward gears and one reverse.

Somewhat blue in the collar, and trying to avoid the ‘helpful’ advice being

yelled across the track by his main-line counterpart, the Glenthorne driver

checks his watch and quickly makes his way forward to test the railcar’s

brakes; the harbour line features such prolonged gradients as to make the

descent from Woody Bay to Barbrook seem like a Sunday School picnic, and so

tests of the vacuum system are mandatory under the terms of the Harbour

Authority’s Light Railway Order.

As the railcar emits a series of hisses and thuds, across the way 303

continues to idle powerfully and confidently, and she has every right to;

indeed this particular unit holds the railway’s ‘speed record’ for a service

train, Minehead to Barnstaple in two hours, twenty minutes (at an average

speed, including station stops, of 20mph). On a non-stop test run conducted

at night, when all signals and points could be set in her favour, unit 305

made the trip in seventy-nine minutes (an average of 35mph throughout). It is

these formidable abilities, combined with the comfort yielded to passengers

by their articulation, that have allowed the railcars to win back local

traffic, thus snubbing the rival buses.

Suddenly, guards on both platforms let out piercing shrieks on their

whistles, and the two railcars yelp back in unison, Now occurs a sight seen

nowhere-else on the network, as the two railcars pull out together, the

harbour train seemingly about to collide with 303, before it suddenly swings

across the points and down the branch towards the harbour, while 303 lets

into the short, sharp climb to the viaduct with a smooth thrum. It’s almost

certain that their drivers (both younger men) will be itching to see which

can reach Doone first, and in all likelihood, the passengers will be egging

them on, but safety always comes foremost and so any ‘racing’ will most

assuredly be of a ‘tame’ nature.

It is such moments that lend County Gate the title of ‘busiest station on the

railway’ in the summer months, and yet once the two railcars have vanished

out of sight (roaring their horns in the distance as they cross at the

viaduct), abrupt silence falls on the station as surely as a muffling

blanket.

Now, we may explore